What is Food Fraud?

You may not have heard the term ‘food fraud’ before, however, do you remember the horsemeat scandal that shocked the UK in 2013? This is possibly the most notorious example of food fraud publicised in recent years. During the aftermath, questions were raised concerning the legitimacy of what we are selling and consuming.

Seemingly, there haven’t been other instances of fraudulent foods as prolific as the horsemeat incident so we may feel as though this is no longer an issue.

In fact, food fraud is far from solved.

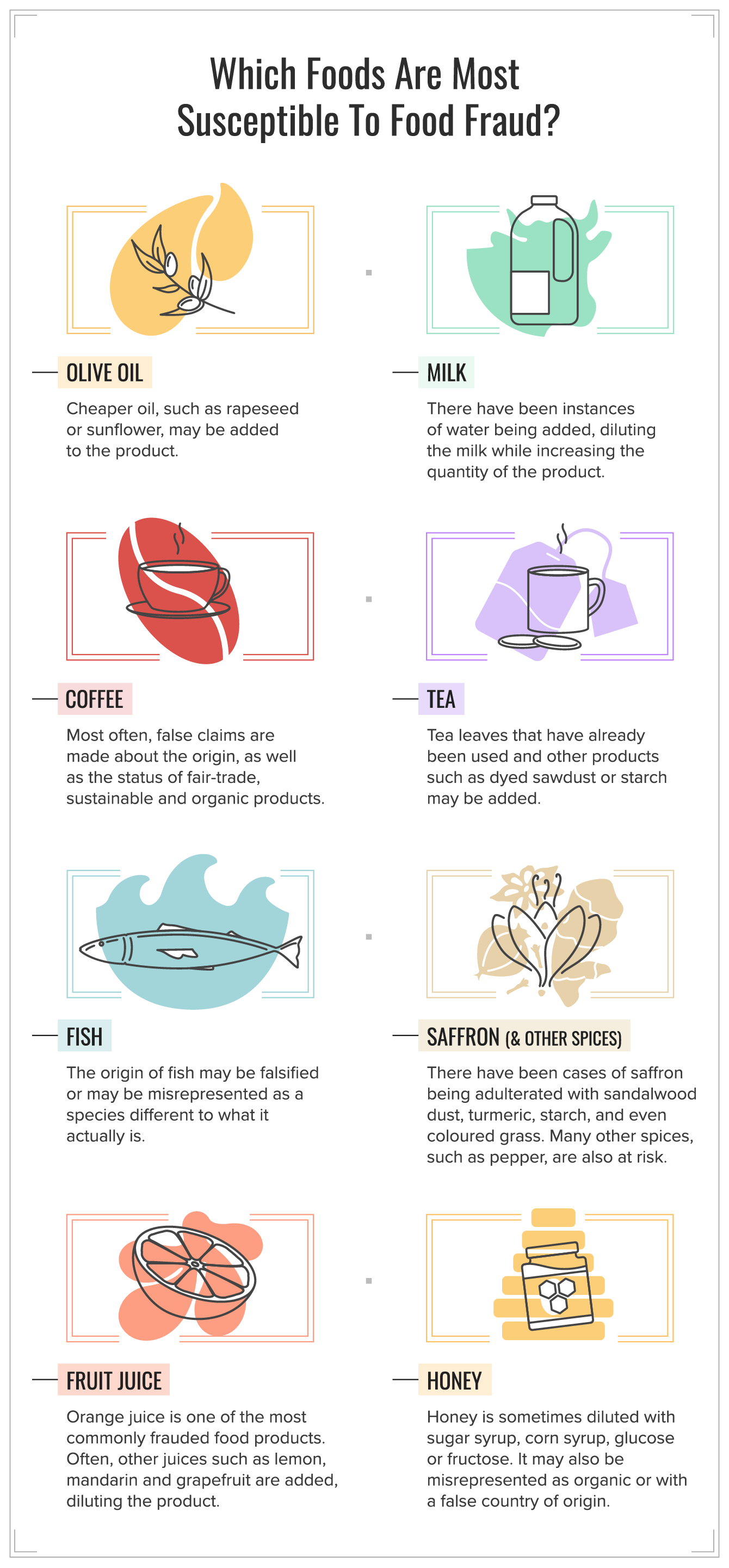

Which Foods Are Most Susceptible to Food Fraud?

- Olive oil. Cheaper oil, such as rapeseed or sunflower, may be added to the product.

- Milk. There have been instances of water being added, diluting the milk while increasing the quantity of the product.

- Coffee. Most often, false claims are made about the origin, as well as the status of fair-trade, sustainable and organic products.

- Tea. Tea leaves that have already been used and other products such as dyed sawdust or starch may be added.

- Fish. The origin of fish may be falsified or may be misrepresented as a species different to what it actually is.

- Saffron (and other spices). There have been cases of saffron being adulterated with sandalwood dust, turmeric, starch, and even coloured grass. Many other spices, such as pepper, are also at risk.

- Honey. Honey is sometimes diluted with sugar syrup, corn syrup, glucose or fructose. It may also be misrepresented as organic or with a false country of origin.

- Fruit Juice. Orange juice is one of the most commonly frauded food products. Often, other juices such as lemon, mandarin and grapefruit are added, diluting the product.

What Actually is Food Fraud?

Food fraud is also known as economically motivated adulteration (EMA). The example of the horsemeat scandal is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what it covers. The scandal was actually an example of substitution in that horsemeat was deceivingly sold as beef.

The criminal intelligence unit of the Food Standards Agency (FSA), the National Food Crime Unit (NFCU), defines food fraud as ‘a dishonest act or omission, relating to the production or supply of food, which is intended for personal gain or to cause loss to another party’.

Typically, it is the prospect of monetary benefit that encourages people to commit food fraud at the expense of consumers. However, organisations may also engage in food fraud for other motivations, such as to raise their competitive standing.

If you are involved in the process of sourcing or accepting food, such as for restaurants, cafés, bars, or pubs, you should be aware of the possibility of becoming complicit in food fraud. This article will provide an overview of food fraud, including the different types, legislation, when it can occur and who is responsible.

What are the Most Common Types of Food Fraud?

Type: Adulteration

Definition: An extraneous substance is added to a food product, reducing its quality. This is done to lower costs or fake a higher quality of a product while increasing volume.

Example: In 2008, it was discovered that melamine was being added to milk and infant formula in China. Water had been added to raw milk to increase its volume but this dilution had lowered its protein concentration. Melamine was added to artificially raise the protein concentration. It increases the nitrogen content of the milk, indicating a greater concentration of protein when analysed by companies. However, melamine can cause kidney failure and kidney stones. As a result, six babies died and an estimated 300,000 became ill from the contaminated milk. During this scandal, products adulterated with melamine were detected in confectionery on UK shelves.

Type: Substitution

Definition: Part or all of a food product is replaced with a similar substance without it altering the product’s overall characteristics.

Example: In November 2018, a honey producer in Corsica was charged in relation to substitution. 600 kg of imported honey was mixed with honey produced in Corsica. It was then marketed as a PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) honey, despite being a blend.

Type: Dilution

Definition: A cheaper liquid alternative is added to a high value ingredient, therefore diluting it.

Example: One of the most common foods that is fraudulent is olive oil. Extra virgin olive oil is considered to be high quality and is therefore more expensive than other oils. Factors including increasing prices, limited supply and a low inability to detect inauthenticity make olive oil vulnerable to fraudsters. Often, the product is diluted with other cheaper alternative oils such as rapeseed or sunflower. This increases the quantity of the final product, whilst reducing the quality, deceiving consumers who believe they are consuming pure olive oil.

Type: Misrepresentation (or Mislabelling)

Definition: A product is labelled or marketed to portray its quality, origin, freshness, or safety incorrectly. This deliberate act of deception claims that a product is something it is not, usually for economic gain.

Example: One type of food misrepresentation that is on the rise is that of food sold as ‘organic’ despite it containing non-organic ingredients. This misrepresents the product to the consumer who expects their food to have been produced and sourced in a certain way.

Type: Counterfeiting

Definition: Products or ingredients are illicitly produced as replicas of a real product. This may be attempted by forging or copying the packaging of an authentic product. The intention here is to take advantage of the superior value of the product imitated.

Example: In 2018, Italian authorities claimed that 385,000 kg of hard cheese varieties “Grana Padano” and “Parmigiano” were sold in Canada fraudulently. The varieties were labelled with “Made in Italy” despite this being entirely false. Another incident in 2019 involved a criminal organisation in Florence who counterfeited trademarks and labels of a famous Florence winery intended to be placed on bottles of low-quality wine.

It is highly possible that some of the fraudulent products mentioned in these examples made their way to the UK. Once here they may have been unknowingly used and consumed, potentially making you a victim of food fraud.

How Does Food Fraud Affect Consumers?

How Does Food Fraud Affect Consumers?

- Allergens may contaminate food, for example, if someone with a severe dairy allergy unknowingly consumes a product containing traces, there could be life-threatening consequences.

- False claims are made that a food product is organic, when it can’t actually be classified as such.

- Religious needs may be compromised if products sold as halal and kosher are in fact fraudulent.

- Dietary requirements may be compromised, such as if a vegetarian or vegan consumes something contaminated.

When Does Food Fraud Become Food Crime?

When Does Food Fraud Become Food Crime?

The NFCU defines food crime as ‘dishonesty relating to the production or supply of food, that is either complex or likely to be seriously detrimental to consumers, businesses or the overall public interest’.

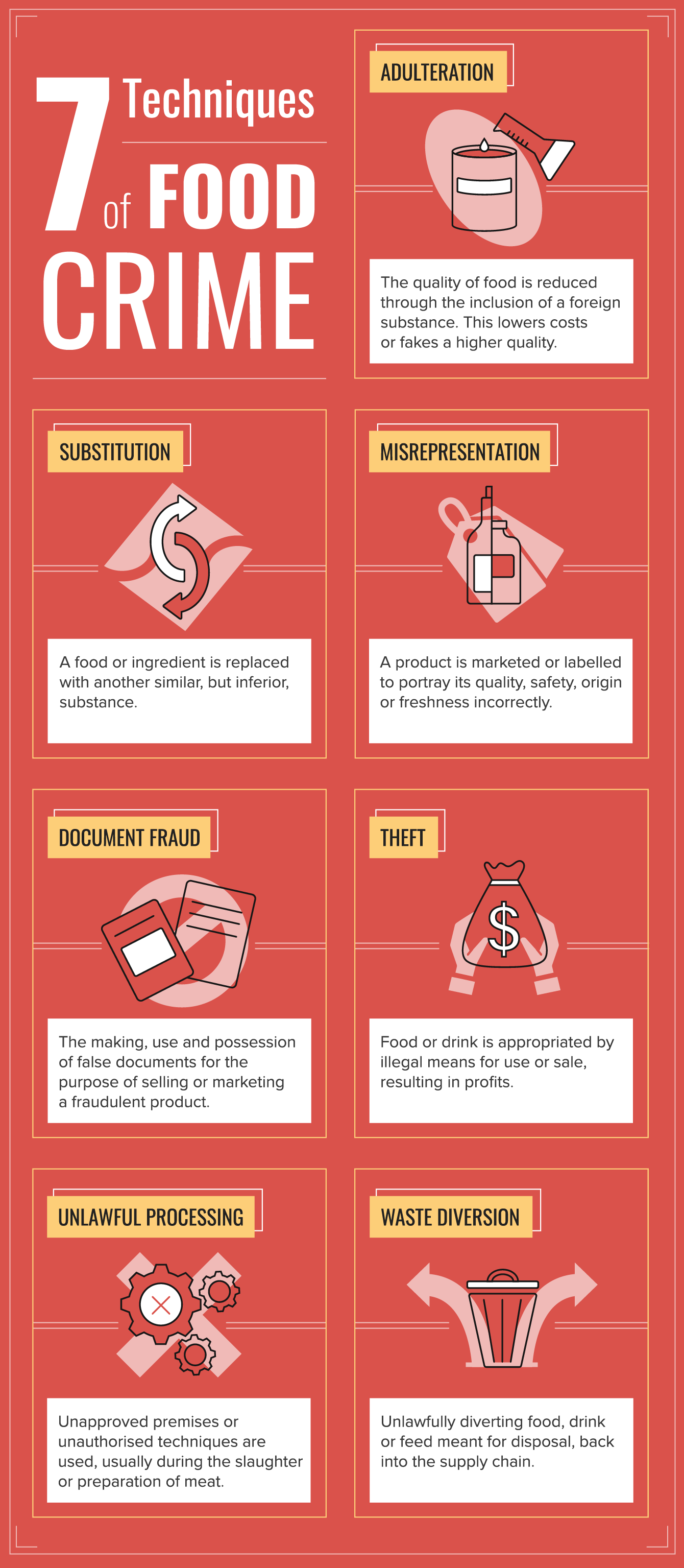

The Unit has identified seven techniques that are the main ways through which food crime is committed.

The National Food Crime Unit has identified seven techniques that are the main ways through which food crime is committed. They are:

- Adulteration – the quality of food is reduced through the inclusion of a foreign substance. This lowers costs or fakes a higher quality.

- Substitution – a food or ingredient is replaced with another similar, but inferior, substance.

- Misrepresentation – a product is marketed or labelled to portray its quality, safety, origin or freshness incorrectly.

- Document fraud – the making, use and possession of false documents for the purpose of selling or marketing a fraudulent product.

- Theft – food or drink is appropriated by illegal means for use or sale, resulting in profits.

- Unlawful processing – unapproved premises or unauthorised techniques are used, usually during the slaughter or preparation of meat.

- Waste diversion – unlawfully diverting food, drink or feed meant for disposal, back into the supply chain.

Food fraud is, therefore, a type of food crime. It becomes considered as such when the scale and possible consequences of the activity are serious. This could be because a risk is posed to public safety or potential financial losses to businesses or consumers.

Food fraud can overlap with other types of food crime. For example, the substitution of beef with horsemeat then led to misrepresentation: another type of food fraud.

Food Fraud and the Law

Food Fraud and the Law

Food fraud is explicitly covered in Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council. This regulation outlines the general principles and requirements of food law, emphasising the importance of food safety. Specifically, Article 8 on the protection of consumers’ interests states that:

Food law shall aim at the protection of the interests of consumers and shall provide a basis for consumers to make informed choices in relation to the foods they consume.

It shall aim at the prevention of:

(a) fraudulent or deceptive practices;

(b) the adulteration of food; and

(c) any other practices which may mislead the consumer.”

– Section 8: Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council

The Food Safety Act 1990 provides the framework for all food legislation in England, Wales and Scotland. The Food Safety Order 1991 provides a similar one for Northern Ireland. Under these regulations, food businesses are required to guarantee that what they sell to the public is of the quality or the substance that the consumer is led to expect. Crucially, they must also ensure that food is advertised, presented and labelled correctly so as to not mislead customers.

In today’s globalised marketplace, protecting consumers from food fraud is an intercontinental task. There are multiple bodies in the UK, including the FSA and NFCU, who share information to help prevent fraudulent activity.

Food crime is a serious issue, costing the UK food industry £11 billion a year. However, legislation is becoming tougher, increasing public awareness and making it harder to get through legal loopholes. If you knowingly commit food fraud then the consequences can include prosecution, resulting in fines and potential jail time.

How Does Food Fraud Happen?

How Does Food Fraud Happen?

For food fraud to happen, there has to be some vulnerability in the food supply chain. Usually, food fraud is committed when there are opportunities and motivations to do so, and control measures are either poor or absent. This lack of sufficient control measures then leads to a vulnerability that allows food fraud to take place.

There are three key components that give rise to food fraud vulnerability:

- The presence of opportunities. This refers to whether there is any chance that food fraud could happen. The level of opportunity depends on two things: the ease to commit fraud and the difficulty of detection. The ease to commit fraud depends on things like the food’s composition, physical qualities, and geographical origins. The difficulty of detection covers the likelihood of the fraudster being caught.

- The existence of motivations. Food fraud wouldn’t happen if there was no motivation behind it. Common motivations for food fraud include economic factors, financial benefit, cultural influences, and behavioural factors. For example, a high value food, which can be diluted by adding a cheaper ingredient but sold at the same price, would create the kind of large profit margin that is motivating to fraudsters.

- The absence of control measures. If a food fraudster recognises the opportunity for, and has the motivation to commit food fraud, then the absence of suitable control measures gives them the opportunity to do so. Control measures, by definition, are something that a company puts in place to minimise risks. This includes measures such as fraud monitoring and verification procedures, whistleblowing guidelines and protection, and legal enforcement. When these things are inadequate, or missing, they provide a catalyst for food fraud to occur.

When Does it Occur?

When Does it Occur?

Food fraud can occur at any stage in the food supply chain. This includes from the early stages such as harvest, through the manufacturing, packaging, and distribution processes, until the preparation and serving of the final food product. However, it is most likely to take place near the start of the supply chain as there are more opportunities to interfere with the product.

Consider the horsemeat scandal, for example, during which the product became fraudulent when it was misrepresented as beef. To this day it is still uncertain as to where exactly the fraudulent activity began. It could have taken place with mislabelling during the initial stages of supply, or during the manufacturing process, but is incredibly difficult to determine. Past incidents of food fraud have shown how there is a serious issue concerning the traceability within the food supply chain.

Who is Responsible?

Who is Responsible?

Everyone who is involved in the supply chain is responsible for ensuring food isn’t tampered with. Potentially, food fraud can take place at any point at which there is opportunity to do so, from farm to fork. Food deliveries are particularly high risk, such as those accepted by restaurants, cafés, bars, pubs and supermarkets. It can be difficult to identify a fraudulent food as they are often extremely similar to the real thing.

An important way to prevent food fraud is to ensure that the suppliers you use are trusted and have strict control measures in place. In the hospitality sector, owners, managers, proprietors and supervisors are usually responsible for sourcing the food and making decisions about which suppliers to use. Supermarkets are also susceptible to food fraud and so procurement buyers must have knowledge of the risks. If this is your duty, you must carry out sufficient research and checks into the company before entering into a partnership. If you serve a customer food with just one fraudulent ingredient, it could have drastic consequences.

Case Study: Pret a Manger

Pret a Manger has recently been in the news due to their mislabelling of food that contained undeclared allergens. In 2017, Pret customer Celia March tragically died after eating a flatbread contaminated with dairy yoghurt despite the product being labelled as dairy-free. Pret argued that the company, CoYo, who supplied the yoghurt that was then used to make the flatbread, were to blame for mislabelling their product as free from dairy. In February 2018, it was revealed that some of CoYo’s yoghurts were contaminated with dairy. However, as of October 2018, CoYo has continued to deny Pret’s claims that they are responsible. This example demonstrates how severe the consequences of misrepresenting a food product can be and how traceability within supply chains must be closely monitored and controlled. Here, the debate continues over which company is actually legally responsible.

The incident is not the only one of its kind to make headlines in the last few years and shows just how crucial it is to carry out thorough checks. Choose suppliers with a transparent supply chain who demonstrate the same commitment to preventing food fraud. Ideally, you should be proactive in checking products yourself, especially for foods containing allergens, if you have the means to do so.

What’s Next for Food Fraud?

What’s Next for Food Fraud?

We have seen how food fraud poses a serious risk to your consumers and your company. You are responsible for doing everything you can to ensure that the foods you source and sell to consumers are safe and are actually what you claim them to be. The general public is becoming increasingly conscious about where their food comes from and what it actually contains. Media reporting of the horsemeat scandal and fatalities following allergen misrepresentation, for example, are making food fraud more topical than ever.

Failure to ensure food is not fraudulent may result in legal repercussions, as well as proving detrimental for your business.

Here at High Speed Training, food hygiene and safety are paramount to our customers, many of whom work in the hospitality sector. Food fraud is a massive threat to food safety and we will continue to investigate the issue in this series.