The Importance of Phonemic Awareness: Teaching Strategies

There are many skills a child needs to develop before successfully learning to read and write. Children need to be aware of how sounds work and how these relate to words before they can fully develop reading and writing skills.

Enjoying a range of books helps to develop children’s vocabulary, sparks an interest in print, supports comprehension, and develops an enthusiasm to have a go at writing, as well as helping with their literacy skills. Phonemic awareness is important if a child is to learn these skills.

How Do Children Learn to Recognise and Spell Words?

With an estimated one million words in the English language, learning to read and spell every word by sight would be an impossible task. This is where decoding and encoding become essential – linking the written letter (grapheme) to their sound (phoneme) and recognising how these combine to make words. If children are unable to decode words, then they will struggle to read fluently and understand what they are reading, and to hear and identify the sounds in words they wish to write.

This highlights the importance of phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear and manipulate phonemes (letter sounds). Children need to become aware of how the sounds in words work, and this can then help to develop skills like reading and spelling. In this article, we will outline what phonemic awareness is, how it relates to reading and spelling, provide some strategies for teaching and look at some of the difficulties some children face with phonemic awareness.

What is Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness and involves identifying and manipulating the individual sounds in words.

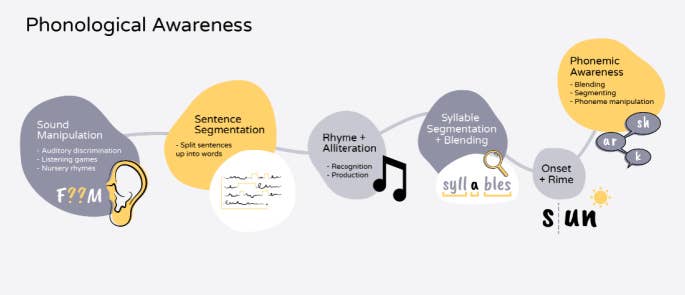

Phonological awareness develops in the preschool years, and is a good predictor of future reading and spelling abilities. Children need to develop their phonological awareness before they can learn to read and spell. Phonological awareness is the process of working out the sounds within spoken language, and includes picking out rhyming words, recognising alliteration and counting syllables in a word.

The diagram below shows the process of phonoligcal awareness:

Why is Phonemic Awareness Important?

Recognising that words are made up of discrete sounds, and that those sounds can be changed, is essential for success in learning to read and spell. Similarly, understanding the connection that words are made up of phonemes and that phonemes are represented by graphemes is a vital skill for understanding print. Being able to take words apart, put them together again and adapt them into a new word (or even a nonsense word!) is a fundamental skill.

There would not be much benefit to teaching children new grapheme phoneme correspondences (GPCs) without some awareness of how they combine to make a word. Reading with a child would involve listening to them string out individual letters, without any meaning, and writing with a child would end up with them having to be told which letters they need to write. This would be a stressful and frustrating situation for all.

There is, of course, a time and a place for learning words by rote, for example ‘tricky words’ or ‘common exception words’, but the strategies for learning these would not be effective for learning to read and spell every single word.

How Does Phonemic Awareness Relate to Reading and Spelling?

The Simple View of Reading (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) is a useful model demonstrating how word recognition and comprehension are essential for learning to read.

Acquisition of these two abilities requires the development of more specific skills:

- Phonemic awareness: the ability to identify and manipulate the distinct individual sounds in spoken words.

- Phonics: the ability to decode words using knowledge of letter-sound relationships.

- Fluency: reading with speed and accuracy. Being able to read automatically, accurately and quickly is an important skill when learning to read.

- Vocabulary: knowing the meaning of a wide variety of words and the structure of written language.

- Comprehension: understanding the meaning and intent of the text.

A child who struggles with one of these interrelated skills, such as phonemic awareness, is likely to have a poor reading ability.

There are six different types of phoneme awareness skills. The first three normally develop first with the last three taking a little longer to master:

- Isolating phonemes: what is the first/ last sound in ‘cat’? (c/t)

- Blending phonemes: blend the phonemes together to make a word, for example “r-u-g” (rug)

- Segmenting phonemes: separate the phonemes in a word, for example mop (m-o-p)

- Deleting phonemes: say “snail” now say it without the ‘n’ (sail)

- Adding phonemes: say “lap” now put a ‘c’ at the beginning (clap)

- Substituting phonemes: change the ‘c’ in cat to ‘b’ (bat)

Oral blending and oral segmenting are the main aspects of phonemic awareness and are very important skills to develop when learning to read and spell.

Oral Blending focuses on the sounds we hear, rather than the words we see. It is when you blend phonemes together to make a word, and is a precursor for blending to read words. For oral blending you need to push the letters together to say the word, for example:

- “Can you find the h-a-t?” and you find the hat.

- “Can you touch your “ch-i-n?” and you touch your chin.

Oral Segmenting focuses on the sounds we hear, rather than the words we see. It is when you separate the phonemes from a word, remembering the order in which they occur. It is a precursor for segmenting to spell words. For this you need to stretch the word out to hear the sounds, for example:

- “What sounds can you hear in the word box?” and the answer is “b-o-x”.

- “What sound can you hear in the word book?” and the answer is “b-oo-k”.

Strategies for Teaching Phonemic Awareness

Some children will develop the phonemic awareness incidentally, picking it up through phonological and other listening games and activities, while others may need it to be taught explicitly.

Often children find the concept of orally blending and orally segmenting more meaningful and interesting if the activity involves a puppet, like an alien or a robot, and to communicate with it you need to use ‘sound talk’ or ‘robot talk’.

Things to remember when teaching phonemic awareness are:

- It is important for children to hear lots of modelling of these skills, before being asked to do it themselves.

- Most children learn to orally blend words before they can orally segment, and when learning to segment, they may not hear and say all the phonemes in a word. For example, for the word cup, they may say “c-p”.

- Ideally, they should grasp the concept of phonemic awareness, or at least show some understanding of it, before learning grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs).

- Continually working on phonemic awareness and other phonological activities alongside teaching phonics is important.

- Stick to cvc words (consonant vowel consonant) at first, but remember that these don’t just include words like hat and van, but also words like sheep (sh-ee-p) and chick (ch-i-ck).

- Activities should be enjoyable and engaging; children should want to do the activity again. Remember, creating a positive attitude towards reading and writing is essential to build on these skills.

- Phonemic awareness can be developed without any written word. Making activities multi-sensory and practical is important, especially with younger children or those with SEND.

Games and Activities to Support Phonemic Awareness

Games and activities can be useful for supporting phonemic awareness. For these activities, start off with blending the phonemes to say the word. As the child’s skills for this improve, they can have a go at segmenting the words for others to blend and to carry out the instruction.

Some games and activities you can try include:

- I Spy: look for items in the classroom, on a poster or on a jigsaw as a prop. Then, instead of using just the initial phoneme, segment the whole word. For example, say “I spy with my little eye a h-or-se” and then let the child find a picture of a horse.

- Can you touch your…: ask the child to touch various parts of their body, for example their “h-ea-d”, “ch-ee-k”, “ch-i-n” and “l-e-g”.

- Classroom instructions: ask the child “Can you find your ch-air?” and “Can you find your c-oa-t?”.

- Tap your shoulder if you hear…: children tap their shoulder if they can hear a certain sound. For example “Tap your shoulder if you can hear an ‘a’ sound in these words – hand, apple, ant, dog”.

- Sound jump: say a word then jump forward for each phoneme in a word.

As children’s ability to orally blend and segment improves, you should begin to model with words. Here are some examples of activities where the child blends and segments the words:

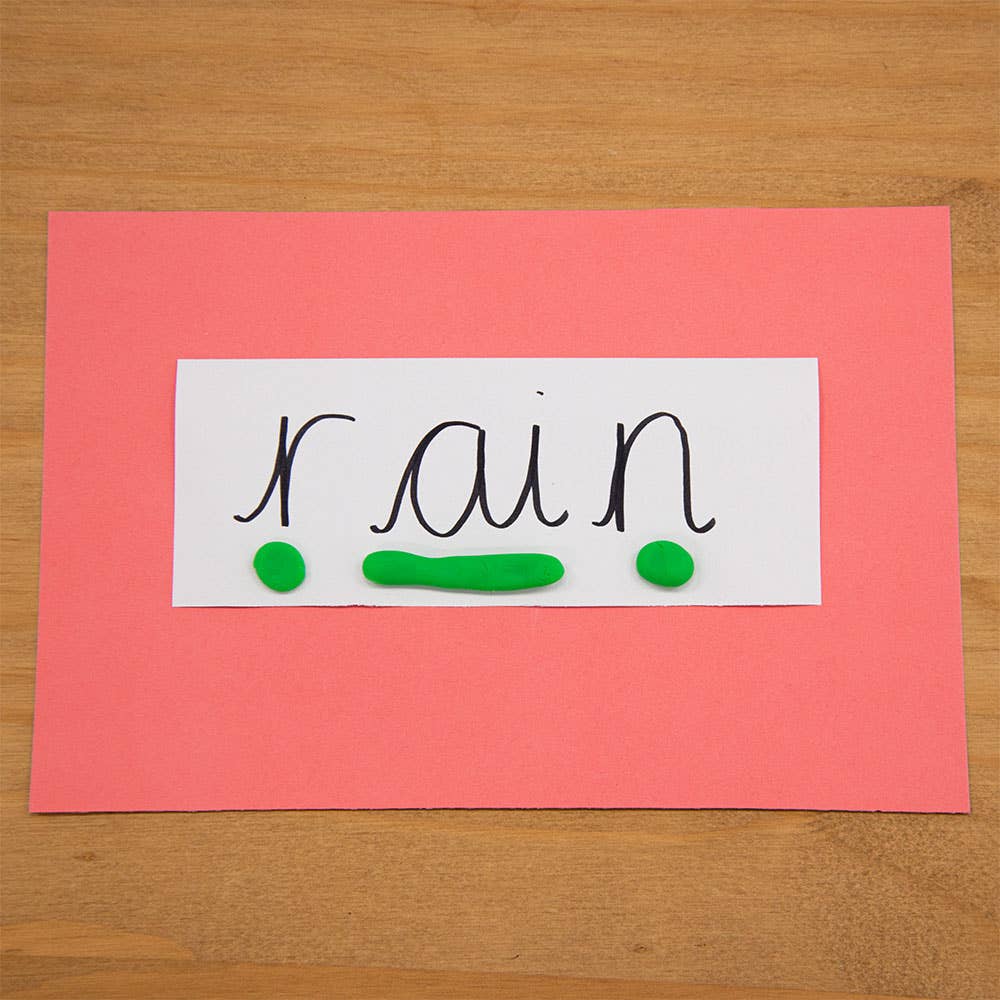

Sound buttons and phoneme frames: split words up into their phonemes and sound buttons.

Full circle: change one letter at a time to make a new word each time, until you have gone full circle. For example, using the letters s,a,t,p,i and making sat, sit, sip, tip, tap, sap, sat.

Washing line: peg out letters in the wrong order for children to rearrange.

If a Child is Struggling with Phonemic Awareness

If a child you are working with seems to be struggling with phonemic awareness, they may not be developmentally ready yet. If this is the case, it is worth spending some time focussing on listening games, and other phonological games and activities.

Listening games include:

- Using instruments to keep a beat and compare the pitch and tone.

- Environmental sound walks: going for a walk and listening to sounds in the environment.

- Body percussion and voice sounds: for example, make your voice sound like: a ball – “boing boing”; going down a slide – “wheeee”; and a train – “chchchch choo choo!”

Other phonological awareness activities include:

- Word awareness: count the words in a sentence, or clap or stamp each word in a sentence, for example in “A frog on a log”.

- Alliteration: identifying, and later producing, words that begin with the same sound, and making silly sentences like “an angry alligator ate all Abby’s apple!”.

- Rhyming: identifying, and later producing, words which have the same endings. For example, looking at pictures of a cat, bat, hat and dog and finding the words which rhyme.

- Syllable Awareness: clapping or tapping parts of a word into syllables, such as children’s names. For example, ‘A-lex-an-der’ would have four claps.

There are many more examples of listening games available in Phase 1 Letters and Sounds Guidance, as produced by the Department for Education.

Factors that can Affect a Child’s Phonemic Awareness

There are a number of factors that can affect a child’s phonemic awareness. Firstly, check that the child is pronouncing the phonemes correctly. There is a tendency for people to put an ‘uh’ sound on some phonemes, for example, “cuh” rather than “c” and “duh” rather than “d”. This leads to a struggle to blend phonemes: for example with the word cat, instead of blending “c-a-t”, they may attempt “cuh-ahh-tuh”, making “cuhahhtuh”, which can cause confusion as it’s not a word.

Other factors which can affect a child’s phonemic awareness include:

Hearing difficulties: most children have a hearing test in their first year of school, though temporary hearing loss following a cold and glue ear are common. Hearing tests can be organised at any time by speaking to the child’s GP, school nurse or health visitor. There’s more information on hearing tests for children on the NHS website.

Speech and language difficulties: a child may have difficulty pronouncing sounds and words correctly. If this is the case they may need a Speech and Language Therapy assessment, which again can be organised through the child’s GP, School Nurse or Health Visitor. There’s more information on speech and language assessments on the ICAN website.

Dyslexia: dyslexia is a learning difficulty which primarily affects accurate and fluent reading and spelling. One the characteristics of dyslexia is poor phonological awareness, and children with dyslexia will often need extra support.

Autism: some children with autism have speech sound difficulties or auditory processing disorders. Many children with autism are visual thinkers, and find abstract concepts like oral blending and segmenting difficult to grasp. They are more likely to benefit from using concrete objects, like magnetic letters. Remember to avoid long verbal explanations.

Working memory: working memory is the ability to hold and manipulate information in the mind for a short period of time. There is evidence to suggest that verbal working memory can affect performance of phonological awareness tasks and activities which involve following and recalling instructions, rote learning, singing songs, retelling stories and copying sound patterns. Working memory co-exists with dyslexia, dyspraxia and ADHD, but can also be a stand alone problem.

If you suspect a child you are working with does have difficulties, you should follow the guidance from the SEND Code of Practice (2015) – The Graduated Approach, of Assess, Plan, Do, Review.

Further Resources

- The Importance of Routine for Children: Free Weekly Planner

- Why is Reading so Important for Children?

- How to Help a Child with Dyslexia in the Classroom

- Why is Reading so Important for Children?

- What is Visual Literacy?

- Education Training Courses